16-05-2007 // MOS Technology - 1974 to 1976

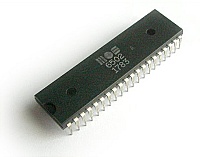

Up until the Commodore Amiga 1000, all Commodore computers featured a chip from MOS Technology at their core. MOS Technology was formed by disgruntled ex-motorola engineers, led by Chuck Peddle This excerpt of On the Edge deals with the trials and tribulations of Chuck Peddle and his men in getting their first chip, the MOS 6502, out in the market.

Selling the revolution

The team now had hundreds of working microprocessor chips, but their battle was just beginning. "We brought it out on schedule, on cost, and on target,” says Peddle. With almost no budget for advertising, it would be up to Peddle and his team to create as much fanfare as possible.

“We wanted to launch the product in a spectacular way because we were a crummy ass little company in Pennsylvania,” explains Peddle. At first, he attempted to garner free publicity from newspapers. “Some people liked the story and put us on the cover of their newspaper, which hyped us up,” he recalls.

Prior to launching the 6502, MOS Technology hired Petr Sehnal, a friend of Chuck’s from his days at GE. “Petr was a Czechoslovakian intellectual who came over to this country,” recalls Peddle. “He was kind of acting as a program manager and getting everything ready for the show, and he was the West Coast sales manager.”

To reach their target audience, Sehnal wanted to take the 6502 to the masses. The annual Western Electronic Show and Convention (Wescon) was showing in San Francisco in September. Sehnal knew the show would be the best place to launch Peddle’s revolutionary new product.

The microprocessor would be useless to engineers without documentation. Peddle recalls, “We were coming down to launching, and my buddy [Petr Sehnal] kept telling me, ‘Chuck, you’ve got to go write these manuals.’ I kept saying, ‘Yeah, I’ll get around to it.’” Peddle did not get around to it.

With Wescon rapidly approaching, and no manual in sight, Sehnal approached John Pavinen and told him, “He’s not doing it.”

“John Pavinen walked into my office with a security guard, and he walked me out of the building,” recalls Peddle.

According to Peddle, Pavinen gave him explicit instructions. “The only person you’re allowed to talk to in our company is your secretary, who you can dictate stuff to,” Pavinen told him. “You can’t come back to work until you finish the two manuals.”

Peddle accepted the situation with humility. “I wrote them under duress,” he says. Weeks later, Peddle emerged from his exile with his task completed. The 6502 would have manuals for Wescon.

The team planned to sell samples of the 6501 and 6502 microprocessors at Wescon, along with the supporting chipset. “We then took out a full-page ad that said, ‘Come by our booth at Wescon and we’ll sell you a microprocessor for twenty-five dollars.’ We ran that ad in a bunch of places,” recalls Peddle. The most prominent advertisement appeared in the September 8, 1975 issue of Electronic Engineering Times.

Things were going well until his team arrived for the show. Peddle recalls, “We went to the show and they told us, ‘No fucking way you’re going to sell anything on the floor. It’s not part of our program. If we had seen these ads we would have killed you.’”

Having come so far and worked so hard, Peddle and his team were not ready to give up. “They told us this just enough in advance that we took a big suite, the McArthur Suite, at the St. Francis Hotel,” says Peddle. MOS Technology would sell their contraband microchips from booth 1010 by redirecting buyers to a pickup location, much like drug dealers.

“People would come by the booth and we’d say, ‘No you can’t do it here. Go to the McArthur Suite and we can sell you the processors,” recalls Peddle. “We became so popular people would get on the bus at the convention center and ask, ‘Is this the bus to the McArthur suite?’”

The promise of low-cost microprocessors caused a sensation. Many people thought the $25 chip was a fraud or assumed it performed poorly. Peddle was confident these questions would resolve themselves once people started using his chips.

Eager hobbyists and engineers lined up in the hall outside the McArthur Suite. Chuck's wife Shirley greeted the engineers, collected their money, and handed out chips. “My very pretty wife was sitting there, and we had this big jar full of microprocessors,” recalls Peddle. “You walked up, we would take your microprocessor off the top, and she would put it in a little box for you.”

The large jars full of microchips seemed to indicate MOS Technology was capable of fabricating large volumes of the 6502 chip. This was subterfuge. “Only half of the jar worked,” reveals Peddle. “The chips at the top of the jar were tested and we knew the ones on the bottom didn’t work, but that didn’t matter. We had to help make the jar look full.”

Shirley Peddle also sold manuals and support chips. Peddle explains, “You could buy this little RAM/ROM I/O device for another $30 and we would sell you the two books we wrote, which turned out to be very popular.”

The manuals gently introduced readers to the concepts of microprocessor systems, explaining how to design a microprocessor system using the 6500 family of chips. It was a bible for microcomputer design. “Everyone told us how good they were to use,” he recalls. “We were very proud of that.”

After completing their purchases, customers entered the suite. Here, Peddle demonstrated the 6501 and 6502 chips, along with tiny development systems such as the TIM and KIM-1 microcomputers. “They would go around the suite and they would see the development systems, and they would find out how to log onto the timesharing systems so they could develop code,” he says. “Then they would wander away.”

The purpose of selling the chips at Wescon was not to raise money. It was to cultivate developer interest in the chip. If all went well, the engineers and hobbyists would go out into the world and design products with the 6502. Waiting in line outside Chuck's hotel room was Steve Wozniak, who thought he might be able to use the chip for a homebrew computer project. Peddle’s documentation undoubtedly influenced Wozniak.

In the months that followed, engineers and hobbyists began reporting success with the MOS microprocessors. Thanks to a review in the November issue of Byte magazine, the chips soon gained a larger following. Dan Fylstra, founder of the company that would someday sell the legendary VisiCalc spreadsheet, wrote an article titled, ‘Son of Motorola’. People soon became convinced that the 6502 chip was a legitimate microprocessor.

The 6502 did not immediately improve MOS Technology’s finances, but it had a major impact on the computer industry. “It spawned a whole class of users, called hackers back then,” says Charpentier.

“It changed the world,” says Peddle. In September 1995, as part of their 20th anniversary edition, Byte magazine named the 6502 one of the top twenty most important computer chips ever, just behind the Intel 4004 and 8080.